This is the second of a series of posts which examine the views of the controversial Jesus Seminar on the resurrection of Jesus. Part One can be found here. Unless otherwise indicated, all page references are from Bernard Brandon Scott (editor), The Resurrection of Jesus, A Sourcebook, Jesus Seminar Guides, Polebridge Press, California, 2008.

The fourth century Christian historian Eusebius recorded that around 200AD, Serapion, Bishop of Antioch, heard about a Gospel of Peter. However, when Serapion read it, he decided that it was heretical and had been written by Docetists who denied the physical side of Jesus’ nature and claimed that he only seemed (dokein in Greek) to be human (Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History, 6:12).

In 1886 fragments of a Gospel of Peter, which can be read here, were discovered in Akhmim, Egypt. Because there does not appear to be anything Docetic about the Akhmim Gospel of Peter, we cannot be completely sure if this is the same Gospel of Peter which Serapion read.

Compared to the rather straightforward New Testament Gospel accounts, the resurrection in the Gospel of Peter contains fanciful and legendary details. A crowd had gathered on Sunday to see the tomb. A giant Jesus comes out of the toms, accompanied by a talking cross. This was all witnessed by the Roman soldiers who told Pilate. Mary Magdalene and the other women came later (Gospel of Peter 9-12).

Jeremiah Johnston has suggested that the “Gospel of Peter” was not meant to be a Gospel at all, but is a second century Christian novel (Jeremiah Johnston, The Resurrection of Jesus in the Gospel of Peter, T. and T. Clark, London, 2018, pp. 178, 189).

Most Bible scholars, conservative or liberal, agree that the Gospel of Peter is a late document which has been embellished and has little, if any, historical value. Nevertheless, the Jesus Seminar Sourcebook devotes a whole chapter to it, “Resurrection Texts in the Gospel of Peter” by Arthur Dewey. The Jesus Seminar, which apparently prefers the unconventional over the conventional, seems to devote more attention to the Gospel of Peter than any of the New Testament Gospels.

Like John Dominic Crossan in The Cross That Spoke (1988), Dewey suggests that parts of the Gospel of Peter are very early and have been built around and embellished. However, his attempt to reconstruct the supposed original text is largely speculative and unprovable (pp. 64-72).

Dewey suggests there was an original version of the empty tomb story which predated both the Gospels of Mark and Peter (p. 72) and involved women going to the tomb and finding it empty (p. 74). This contradicts other Jesus Seminar contributors who say that Mark invented the story of the empty tomb (pp. 46, 82, 98). If Dewey is correct, it would mean there is more early evidence for the empty tomb than most scholars assume.

In Chapter Five, “Was Jesus’ Resurrection an Historical Event?’, which was based on a 2008 debate with William Lane Craig, Roy Hoover seeks to explain the origin of Christian belief in the resurrection and “what early Christians meant when they claimed that God raised Jesus from the dead.” (pp. 75-76)

Hoover says that because the Jews had faith that they would be resurrected, Christian belief in Jesus’ resurrection “began as an affirmation of faith” (p. 78), “an affirmation of faith and hope in the face of the stark, disconfirming fact of his crucifixion, when in spite of his confident message about the Empire of God, Jesus of Nazareth was eliminated by the Empire of Rome.” (p. 78)

The Jews believed they would be resurrected in the future at the end of the age. It is plausible that Jesus’ Jewish disciples would have believed that Jesus would be resurrected in the future along with everyone else. That does not explain why Jesus’s disciples came to believe that his resurrection had already happened, if nothing had happened to encourage this belief, such as an empty tomb and the risen Jesus appearing to them.

There were other Jewish martyrs, messianic pretenders, prophets and crucifixion victims. None of their followers inspired by Jewish hope in the future resurrection, had an affirmation of faith which produced a belief that they had already risen from the dead. The early Christians alone had faith that Jesus rose from the dead. Something must happened to encourage this belief, such as Jesus actually rose from the dead.

Hoover says that “the faith that God raised Jesus from the dead generated the empty tomb stories, the empty tomb stories did not generate that faith.” (p. 80) This is the opposite of the historical evidence says happened. They found the tomb empty, saw the risen Jesus and then believed or had faith that he had risen from the dead. There was a reason, a cause for their belief. This makes more sense than Hoover’s hypothesis that the disciples decided to believe that Jesus had risen from the dead and then decided to make up stories about the empty tomb and his resurrection appearances. Does your mind work like this? if not, why would you think other people’s minds do?

The faith came first hypothesis is not plausible because not everybody who came to believe Jesus rose from the dead had faith in Jesus before they believed he rose from the dead. Jesus’ brother James did not believe in him during his ministry (John 7:5). The risen Jesus appeared to James (1 Corinthians 15:7). He them believed and became a leader in the Jerusalem church (Galatians 1:19). Likewise, Saul did not have any faith in Jesus, but persecuted his followers until the risen Jesus appeared to him (Acts 9:1-9). Again, the evidence says the opposite of what Hoover clams happened.

Hoover inadvertently acknowledges this and contradicts himself. He says some became believers after seeing the risen Jesus when he says the resurrection was a private event, not a public one,

“In the Easter narratives, on the other hand, Jesus appears nowhere in public. the risen Jesus appears only to a select few, all of whom had been his followers or became believers. So the gospel authors themselves indicate in the way they tell the Easter stories that the resurrection of Jesus was not an historical event in the ordinary sense of the term: it was not something open to public observation or verification”(p. 80).

Private events are still historical events. However, not all the resurrection appearances were private. Jesus appearing to 500 people at one time sounds like a public event (1 Corinthians 15:6). Other people saw the light when Jesus appeared to Paul on the road to Damascus (Acts 22:9). It was not a subjective inner experience.

The fact that some unbelievers “became believers” after seeing the risen Jesus does not suggest that the resurrection was not a historical event. It only shows how persuasive the evidence was.

Hoover claims that the differences in the Gospels’ accounts of the resurrection “show there is no common tradition between them. Each gospel author was therefore free to compose his own imaginary tale about how it must have been.” (p. 81)

As I have discussed in other posts here and here for nearly 30 years the consensus among New Testament scholars has been that the Gospels are ancient biographies of Jesus. Biographers did not “compose their own imaginary tales”. They recorded what they believed happened in the life of their subject.

The differences in the Gospel accounts show that the writers were not copying a single account. New Testament historians call this the criterion of multiple attestations, which means that the more independent sources there are for an event, the more more historically reliable it is likely to be. The five independent sources for the resurrection (the four Gospels and 1 Corinthians 15), suggest it is very historically reliable.

Another criterion of authenticity is embarrassment, which means that the text contains something embarrassing, it is unlikely that the early Christians would have made it up and it must have happened, i.e., why was the sinless Jesus baptised for the forgiveness of sins (Mark 1:4)? The four Gospels say that the first witnesses to the empty tomb were women. The authors would not have made this up because it is so embarrassing. Women had little credibility as witnesses in the ancient world. If they were going to make up the empty tomb, they would have naturally said the witnesses were men.

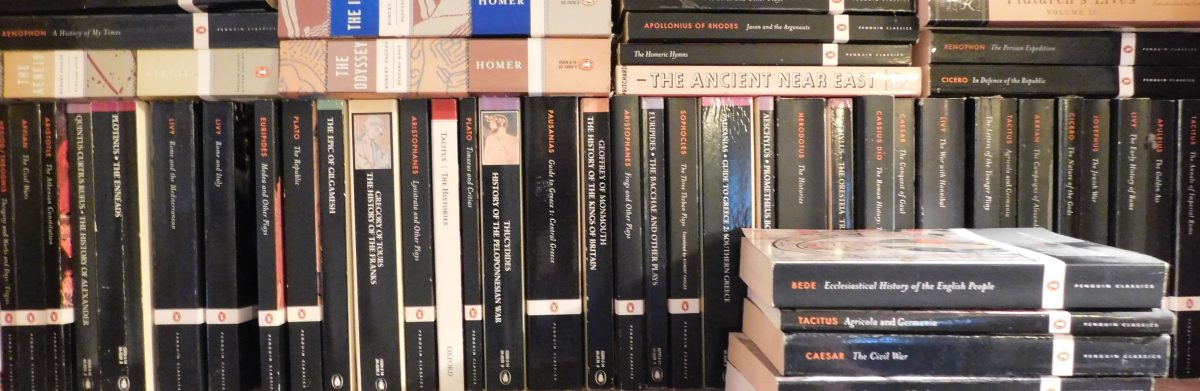

The Jesus Seminar think they are so smart and progressive, yet they do not sound like they are up to date with the trends in historical Jesus scholarship. This is evident when one consults the bibliography in The Resurrection of Jesus, A Sourcebook. It contains The Resurrection of Jesus by Gary Habermas which is for the physical resurrection, The Resurrection of Jesus, History, Experience, Theology by Gerd Ludemann which is against the physical resurrection, and The Cross That Spoke by John Dominic Crossan which promotes the dubious theory that the Gospel of Peter is early (pp. 117-118). The other listed books do not deal directly with the historicity of the resurrection. Scholarly works defending the historicity of the resurrection, such as Assessing the New Testament Evidence for the Resurrection of Jesus (1989) by William Lane Craig, The Resurrection of the Son of God, Christian Origins and the Question of God, Vol. 3 (2003), by N. T. Wright and The Resurrection of God Incarnate (2003) by Richard Swinburne, do not get a mention. To be blunt, members of the Jesus Seminar need to read more books.

Hoover says that the supposed contradictions in the resurrection accounts indicate that “they are nor based on eyewitness accounts of things that actually happened on that Sunday morning.” (p. 83)

Everyone, who deals in eyewitness testimony, historians, journalists, lawyers, knows that eyewitness contradict each other. They are not lying. They just remember things differently. When critics of the resurrection say the differences in the Gospels mean they are not eyewitness accounts or they did not happen at all, they are only exposing how little they understand about history and eyewitness testimony and how unqualified they are to speak on whether or not an event really happened.

Any contradictions in the Gospels would not necessarily mean they are historically unreliable. It would have implications for the doctrines of inspiration and inerrancy. However, the supposed contradictions in the resurrection accounts are not irreconcilable contradictions. Two people can describe the same event differently and both can still be true. I will discuss the supposed contradictions in more detail in Part Three.

Hoover says that Paul was the only New Testament author who claimed to have seen the risen Jesus (p. 82), even though the author of John clearly says that he did too (John 21:24). He agrees that 1 Corinthians 15 shows that Paul heard about the resurrection from Peter in Jerusalem a few years after Jesus’ death. However, because 1 Corinthians 15 does not mention the empty tomb, Hoover claims that Paul and Peter did not know about it and the accounts of the empty tomb and the appearances in the Gospels were made up later (pp. 82-83).

This is the argument from silence. Hoover is assuming that what Paul wrote in 1 Corinthians 15 is everything he knew about Jesus’ resurrection. He does not know how much Paul knew. Do we really think 1 Corinthians 15:3-7 was everything Peter told Paul about Jesus’ resurrection? Paul could have met Mary Magdalene and visited the empty tomb, but he did not mention it.

In fact, if there had not been heretical beliefs about the resurrection among the Corinthian Christians, which he was addressing in 1 Corinthians 15, Paul would not have mentioned what Peter told him at all, and Hoover and other critics would be claiming that Paul knew even less.

Hoover argues, “If the “appearance” stories in the other gospels are factual reports, Mark would have surely mentioned them.” (p. 64) As already mentioned in Part One, this is based on the unsound suggestion that Mark intentionally ended his Gospel at verse 8, when like many ancient manuscripts, the original ending, which probably included a resurrection appearance in Galilee, was lost.

Hoover claims that Matthew and Luke could not have copied Mark, but made up their own resurrection appearances, based on the appearances in 1 Corinthians 15 (p. 85). Huh? 1 Corinthians 15 does not mention the appearances to the women or to the two disciples on the road to Emmaus. It mentions appearances to James and the 500 (1 Corinthians 15:6-7), which are not described in Matthew or Luke. The resurrection accounts in Matthew and Luke are not based on 1 Corinthians 15. We are dealing with multiple independent accounts.

Hoover writes that Paul had “a visionary confirmation of his faith.”(p. 85) This does not make sense. Paul did not have any faith in Jesus to confirm before the risen Jesus appeared to him. He believed Jesus was a deceiver who got what he deserved so he persecuted his followers. His encounter with the risen Jesus changed his mind.

Paul was a member of the Pharisees who believed in physical resurrection. He would have understood that seeing a vision of someone in Heaven does not mean they have physically risen from the dead. Paul understood his experience as an appearance of the resurrected Jesus although he acknowledged that it was different from others’ appearances (1 Corinthians 15:8).

Hoover claims that Matthew and Luke took the visions of Paul, Stephen and others of the risen Jesus in Heaven and “literalized and materialized the idea of such “appearances” [so] they depict a risen Jesus still on earth.” (p. 85) Most scholars would agree that Matthew and Luke were writing independently of each other, yet, according to Hoover, they both decided on their own to turn visions of Jesus in Heaven into accounts of the risen Jesus walking around on Earth. Why would they bother to do this? What was wrong with visions of Jesus in Heaven? Visions of Jesus in Heaven would have been much more acceptable to the pagans which the early church was increasingly trying to win, who found the idea of physical resurrection offensive.

Hoover argues that the “idea of resurrection in Bible’s ancient worldview” (p. 87) in which the Earth was believed to be at the centre of the cosmos and God was believed to be up there above the sky in Heaven. Hoover says this worldview has been disproved by science and “The risen Jesus could not ascend to heaven” because “There is no heaven.” (p. 88) If you see someone who was dead come back to life, it does not matter how big you think the universe is. If God reveals Himself to a pre-scientific culture, that revelation does not necessarily become invalid in a scientific culture.

Nevertheless, Hoover is accurate in that the debate over the resurrection is founded on a clash of worldviews. The Jesus Seminar have a worldview which is not open to the idea that God would intervene in the natural world, so they do not believe God rose Jesus physically from the dead. If the historical evidence conflicts with their worldview, they do not modify their worldview to fit the evidence, they modify or deny the evidence to fit their worldview. This is the sort of dogmatism they are quick to accuse “fundamentalists” of.

Hoover says that although “the idea of resurrection has lost its literal meaning” (p. 89), it is still possible to have resurrection faith or hope which Hoover describes as a continuing belief in justice, virtue and transformation even when they are not apparent in the world (p. 90).

Belief in the physical resurrection of Jesus and in this kind of resurrection hope in this world are not incompatible. It is not an either/or choice. We can believe in both. Because God rose Jesus from the dead, we know this hope is not futile or in vain. It will come true when the risen Jesus returns, sin, suffering and death are defeated and the kingdom of God encompasses everything.

To be concluded on Part Three