British-Israelism or Anglo-Israelism is the belief that the inhabitants of northern Europe, particularly the British Isles, are the descendants of the lost ten tribes of Israel.

After King Solomon died around 931 BC, his kingdom spilt in two. The southern kingdom Judah consisted of Judah, Benjamin and some of the Levites, while the other ten tribes made up the northern kingdom of Israel.

Around 733-732 BC the Assyrians invaded Israel and deported the inhabitants of northern Israel to Assyria (2 Kings 15:29). Apparently at the same time the tribes of Reuben, Gad and Manasseh east of the Jordan were also deported to Halah, Habor, Hara and the river of Gozan in the north of the Assyrian empire (1 Chronicles 5:26). In 722 BC the Assyrians captured Samaria, capital of Israel and “carried Israel away to Assyria, and placed them in Halah and by the Habor, the river of Gozan, and in the cities of the Medes” (2 Kings 17:6). The northern kingdom of Israel had ceased to exist.

The Assyrian empire fell in 603 BC and was replaced by the Babylonians. In 586 BC Nebuchadnezzar, king of Babylon, captured Jerusalem, destroyed the Temple and deported its inhabitants to Babylon (2 Kings 25:1-21, 2 Chronicles 36:15-21).

In 539 BC the Persians conquered Babylon and their king Cyrus issued a decree allowing the Jews to return and rebuild the temple (Ezra 1:1-4). Judah was now a province of the Persian empire and was later conquered by the Greeks and then the Romans.

The fate of the ten northern tribes is less clear. The “lost tribes of Israel”, as they are often called, are assumed to have migrated elsewhere. Some researchers have reported to have found the lost tribes in North or South America, Africa, China, Burma, India, Afghanistan, New Zealand and Japan (Tudor Parfitt, The Lost Tribes of Israel, Phoenix, London, 2002). The most popular theory is British-Israelism which claims the ten tribes went north from Assyria and became the Scythians who became the Germanic Tribes who migrated into western Europe, particularly the British Isles.

British-Israelism is not as popular as it once was in the 19th and early 20th centuries when the British Empire was at its height and its adherents argued that God’s promises to Abraham were now being fulfilled in the English-speaking people. Nevertheless, it still has its supporters, such as the British-Israel World Federation, the Christian Identity movement and the followers of the late Herbert W. Armstrong. There is even a Jewish British-Israelite, Yair Davidiy.

From a Christian perspective, British-Israelism is not necessarily a heresy. In theory, one could believe the British people are Israelites and still believe the at Jesus Christ is the Son of God who died for our sins and rose from the dead. The two beliefs are not incompatible. Indeed, during the movement’s heyday in the 19th century, many of its adherents belonged to the Church of England. Instead, British-Israelism tends to be an obsession, rather than a heresy. It is all its adherents talk about, more than the Gospel of Jesus.

The fundamental problem with British-Israelism is that their claims are not supported by the historical and archaeological evidence. The Bible does not say the Germanic or Scythian tribes were the lost tribes of Israel. However British Israelites often quote a passage from the Apocrypha,

“These are the nine tribes that were taken away from their own land into exile in the days of King Hoshea, whom Shalmaneser, king of the Assyrians, made captives; he took them across the river, and they were taken into another land. But they formed this plan for themselves, that they would leave the multitude of the nations and go into a more distant region, where no human beings had ever lived, so that there at least they might keep their statutes that they had not kept in their own land. And they went in by the narrow passages of the Euphrates river. For at that time the Most High performed signs for them, and stopped the channels of the river until they had crossed over. Through that region there was a long way to go, a journey of a year and a half; and that country is called Arzareth. Then they lived there until the last times; and now when they are about to come again, the Most High will stop the channels of the river again. Therefore, you saw the multitude gathered together in place.” (2 Esdras 13:39-47)

British-Israelites do not usually make it clear, but this is not a historical account. It is part of an apocalyptic vision which is attributed to Ezra who lived in the 5th century BC, although 2 Esdras was probably written in the late 1st century AD.

Even if this passage were historical and meant to be taken literally, it does not support the British-Israel hypothesis. It says it took the tribes 18 months to reach a land where no human beings had ever lived. Northern Europe was already inhabited before the fall of Israel in 722 BC. It cannot mean the Germanic tribes were Israelites because it took them hundreds of years to settle in their present locations.

This passage also says the tribes were going to return to the land of Israel. I doubt it mean all the Europeans are going to “return” to the Middle East.

The first century Jewish historian Josephus did not believe the Scythians were Israelites. Noah had three sons, Japheth, Shem and Ham. Josephus wrote that the Scythians were descendants of Japheth. His son Magog was the ancestor of the Scythians; another son Javan was the ancestor of the Greeks and another son Gomer was the ancestor of the Gauls (Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, 1:6:1). The Israelites were descendants of Japheth’s brother Shem.

The Greek historian Herodotus reports that the Scythians invaded and dominated the Middle East for about 28 years (Herodotus, The Histories, 1:104-106, 4:1 ). Some British-Israelites believe this meant the northern tribes returned to the land of Israel and then left again (Steven Collins, Israel’s Lost Empires, Bible Blessings, Michigan, 2002, p 213-225).

The Old Testament does not necessarily mention everything which happened during the period it covers, but if the northern tribes of Israel had returned home even temporarily less than 100 years after they had been deported, one would expect the Old Testament or other historical sources, such as Josephus, to have mentioned it.

Herodotus wrote that the Scythians believe, “The first man to live in their country, which before his birth was uninhabited, was a certain Targitaus, the son of Zeus and of a daughter of the river Borysthenes” (Herodotus, The Histories, 4:5). Targitaus had three sons, Lipoxais, Arpoxais and Colaxais, the ancestors of the branches of the Scythians.

Herodotus added, “Such is the Scythians’ account of their origin, and they add that the period from Targitaus, their first king, to Darius’ crossing of the Hellespont to attack them is just a thousand years.” (Herodotus, The Histories, 4:7)

The Scythians did not believe they were Israelites or that they had only been in their land for about 200 years, that is, after the Assyrians had deported them in 733-2 and 722 BC. They believed they had lived there for 1000 years.

Herodotus, the Persians or any other ancient source did not say the Scythians were Israelites or related to the Jews. Herodotus said the Persians called the Scythians “Sacae” (Herodotus, The Histories, 7:64). British-Israelites argue that this is derived from Isaac, so the Scythians were Israelites.

British-Israelites often cite God’s promise to Abraham, “In Isaac your seed shall be called” (Genesis 21:12), to argue that his descendants would be named after Isaac. Because “Isaac” and “Sacae” sound similar, the Sacae or Scythians were supposedly named after Isaac and were Israelites (Israel’s Lost Empires, p 197,206-207, William Pascoe Goard, The Post-Captivity Names of Israel, Covenant Publishing Company, Britain, 1943, p 10-11).

The Genesis 21 passage does not mean Abraham’s descendants would be called Isaac. They weren’t. The northern tribes were often called Israel, Samaria or Ephraim, but they are only referred to twice as Isaac (Amos 7:9,16). This passage is about the rivalry between Abraham’s sons Isaac and Ismael. God is saying that His promises to Abraham would be passed on through Isaac rather than Ishmael.

Moreover, the Scythians did not call themselves the Sacae. The Persians did. Herodotus wrote that the Scythians, which the Greeks called them, called themselves the Scoloti after one of their kings (Herodotus, The Histories, 4:6). This does not resemble the name of any Israelite king.

British Israelites claim that the name Saxons is derived from Isaac, so the Saxons were Israelites. Herbert W. Armstrong has written that the Saxons in Germany derive their name from the Old High German “Sahs” meaning “sword or “knife”, which apparently disproves the British Israelite argument. However, Armstrong claimed that the Saxons in Germany “are an entirely different people from the Anglo-Saxons who migrated to Britain” (Herbert W, Armstrong, The United States and Britain in Prophecy, Everest House, New York, p 120-121). Actually, some Saxons migrated to Britain, while other Saxons stayed behind on the European mainland.

The Germanic tribes could not be the lost tribes of Israel because they were already in northern Europe in the 8th century BC before the Israelites were deported. This map from The Penguin Alas of World History shows the Germanic tribes in northern Germany and Denmark. They migrated to the south and east, rather than coming from the south east.

Steven Collins proposes an even more confusing theory. He says the deported Israelites became the Parthian Empire and only migrated to Europe and became the Germanic tribes after the fall of the Parthian Empire in 226 AD, even though Roman historians were writng about the Germanic tribes across the Rhine about 200 years earlier (Steven Collins, Israel’s Tribes Today, Bible Blessings, Michigan, 2005)

The early English historian Nennius wrote in History of the Britons (c. 825 AD) that Japheth’s son Javan was the father of the Germanic nations, including the Anglo-Saxons, and another of Japheth’s sons Magog was the father of the Scythians. Nennius believed the Germanic and Scythian tribes were related. But they were not the same, and they were not Israelites, descendants of Noah’s other son Shem (Nennius, History of the Britons, 17-18).

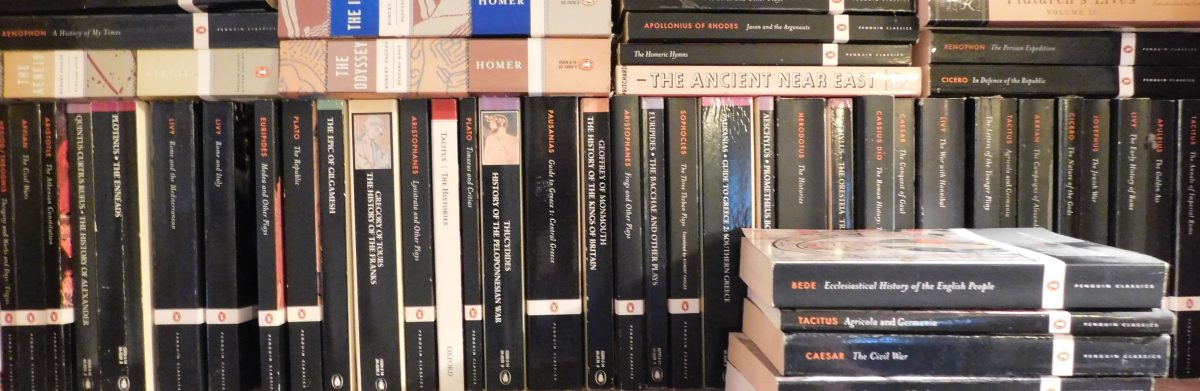

Other early English historians, such as Bede (672-735), author of Ecclesiastical History of the English People, the compliers of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (9th century), and Geoffrey of Monmouth (1095-1155), author of History of the Kings of Britain, did not say anything about the English people being the descendants of the lost tribes of Israel.

Most British-Israelites claim that the tribe of Ephraim is Britain and the Commonwealth nations, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and South Africa, and the tribe of Manasseh is the United States.

When we consider the waves of migrations to Britain, the Angles, Saxons, Jutes, Danes and Normans, it is hard to see how Britain could be identified with Ephraim. It also seems implausible that English immigrants to Canada and other Commonwealth nations were from Ephraim, while those who went to the United States were from Manasseh.

British-Israelites cannot agree on which modern nation should be identified with which tribe of Israel. If we compare Steven Collins, author of Israel’s Tribes Today, and Yair Davidiy, author of The Tribes (Brit-Am Israel, Jerusalem, 2004), they both agree Reuben is France (The Tribes, p 462, Israel’s Tribes Today, p 190-197) and Zebulon is Holland (The Tribes, p 462, Israel’s Tribes Today, p 198-201). However, Collins thinks Asher is South Africa (Israel’s Tribes Today, p 202-3), while Davidiy thinks Asher is Ireland (The Tribes, p 462). Collins thinks Issachar is Finland (Israel’s Tribes Today, p 206-8), while Davidiy thinks Issachar is Switzerland and Sweden (The Tribes, p 462). Collins thinks Gad is Germany (Israel’s Tribes Today, p 218-222), while Davidiy thinks Gad is Sweden (The Tribes, p 462). Their identifications are circumstantial and arbitrary, rather than based on historical evidence.

British Israelites assume the Germanic tribes were Israelites, so the northern Europeans are Israelites, but the Germanic tribes did not all settle in northern Europe. The Visigoths settled in Spain. The Vandals settled in North Africa. The Ostrogoths settled in Italy, Austria, Hungary and the former Yugoslavia. Which tribes are these nations supposed to be?

Moreover, most historians now believe that the Germanic invasions were not so much large-scale population migrations, but were the migrations of smaller elites who replaced the existing elites and dominated the existing populations. (Peter Bogucki and Pam Crabtree (editors), Ancient Europe 8000 BC – AD 1000, Encyclopedia of the Barbarian World, Volume II, Charles Scribners, New York, 2003, p 380)

British-Israelites claim there were earlier migrations of Israelites. In Israel’s Lost Empires Steven Collins claims about 250,000 were supposed to have left during the 40 years in the wilderness (Israel’s Lost Empires, p 102). During the drought of Ahab’s reign (c. 874-853 BC) many Israelites left and “found new homes in Israel’s colonies in Spain, North Africa, the British Isles and even North America.” (Israel’s Lost Empires, p 80)

Collins equates the Phoenicians, who were Canaanites, with Israelites and claims that many of the Celts “were descended from Israelites who settled Phoenician colonies in Europe during the Golden Age of Israel-Phoenicia in 1000-750 BC. Later Celts descended from the many Israelite refugees who fled Palestine to seek new lives in the maritime colonies of Israel.” (Israel’s Lost Empires, p 106)

Collins also writes, “Before the final Assyrian invasion, Israel was the scene of an ancient equivalent of the Dunkirk operation of World War II …. evacuating as much of its population as possible [by sea] to save it from an Assyrian captivity.” (Israel’s Lost Empires, p 98)

Other Israelites are supposed to have escaped the Assyrians by migrating overland to the Black Sea area so the majority of the northern tribes were never taken into captivity by the Assyrians (Israel’s Lost Empires, p 90-96, 111-115).

The Bible or any other ancient source does not say anything about these supposed Israelite migrations. Moreover, the ancestors of the Celts, the Urnfield Culture, were already in Europe as early as 1300 BC, long before these imaginary migrations of Israelites.

British-Israelites also believe there were earlier migrations of Israelites to Britain and Ireland. Judah had twin sons Perez and Zarah (Genesis 38:29-30). The kings of Judah were descendants of Perez. The last king of Judah Zedekiah was deposed by Nebuchadnezzar around 586 BC.

Zarah had five sons, including Dara (1 Chronicles 5:6). E. Raymond Capt believes that Dara was Dardanus, the founder of Troy, so the Trojans were Israelites (E. Raymond Capt, Jacob’s Pillar, A Biblical Historical Study, Artisan Sales, Oklahoma, 1977, p 25-26). His evidence is a fragment from Hectabaeus of Adera (circa. 300 BC) who described how the Egyptians decided to drive the foreigners out of Egypt;

“At once, therefore, the aliens were driven from the country, and the most outstanding and active among them banded together and, as some say, were cast ashore in Greece and certain other regions; their leaders were notable men, chief among them being Danaus and Cadmus. But the greater number were driven into what is now called Judaea, which is not far distant from Egypt and was at that time utterly uninhabited.” (Jacob’s Pillar, p 8)

Canaan was not uninhabited before the Israelites arrived. Hecataeus goes on to say that Moses founded Jerusalem and built the Temple, which suggests he is that historically reliable. Furthermore, Hecataeus did not say that Danaus was an Israelite, only that they left Egypt at the same time as the Israelites.

According to Apollodorus in Library of Greek Mythology, Belos, the son of Poseidon, became king of Egypt and had two sons Danaos and Aigyptos. Danaos had 50 daughters and Aigyptos had 50 sons. Danaos and his daughters fled to Argos where he became king. The sons of Aigyptos followed them to Argos where they demanded to marry the daughters. At the wedding the daughters killed all but one of the 50 sons (Apollodorus, Library of Greek Mythology, 2:2:4-5).

Even if any of this were true, Danaos was not the same person as Dardanos, the founder of Troy. British-Israelites have apparently confused them and thought they were the same. Dardanos was supposed to be the son of Zeus and Electra, daughter of Atlas. He was born on the island of Samothrace and later travelled to the mainland where he married the king’s daughter and founded a city which was later named Troy (Apollodorus, Library of Greek Mythology, 3:12:1).

In History of the Kings of Britain Geoffrey of Monmouth (c.1095-c.1155) wrote that after the fall of Troy, some of the survivors, led by Brutus, migrated to Britain and founded New Troy which was later renamed London. Since British-Israelites mistakenly believe the Trojans were Israelites, this would mean the first Britons were Israelites.

Geoffrey of Monmouth may have believed the Britons were Trojans, but, as we have seen, he said nothing about them being Israelites. Nennius also wrote that Brutus was a Trojan, but he believed Dardanus, the founder of Troy, was the grandson of Javan, the son of Japheth, not his brother Shem, ancestor of the Israelites (History of the Britons, 18).

Some of Zarah’s descendants are supposed to have gone to Ireland (J. H. Allen, Judah’s Sceptre and Judah’s Birthright, Destiny Publishers, Massachusetts, 1902, p 267-268). W. H. Bennett claims they left while the Israelites were in Egypt, but again, there is no historical evidence for this (W. H. Bennett, The Story of Celto-Saxon Israel, The Servant People, Ontario, 2002, p 67-68).

According to Irish legend, the Tuatha De Danann invaded ancient Ireland. British Israelites claim that Tuatha De Danaan means “tribe of Dan” and this legend refers to the tribe of Dan settling in Ireland (Jacob’s Pillar, p 27, The Story of Celto-Saxon Israel, p 77). Actually, it means people of the goddess Dana or Danu (Wikipedia).

Modern historians regard the Tuatha De Danaan and the Milesians, discussed below, as mythological, not historical. They do not believe these invasions happened. Furthermore, the Irish sources for these myths, such as the Book of Invasions or Lebor Gabala Erenn (10) and The History of Ireland by Geoffrey Keating (p 74, 90) did not believe they were Israelites or descendants of Shem. The Tuatha De Danaan and other races, which settled in Ireland, were believed to have been descendants of Japheth’s son Magog. Geoffrey Keating wrote that “every invasion which occupied Ireland after the deluge is of the children of Magog” (The History of Ireland, p 74)

Later, the Milesians supposedly invaded Ireland and disposed the Tuatha De Danaan who withdrew into the Otherworld. This does not sound historical. Steven Collins claims the Milesians were from the tribe of Simeon who left the Israelites during the 40 years in the wilderness (Israel’s Lost Empires, p 99-102). Again, the Bible does not say this happened.

W.H. Bennett claims the Milesians came from Miletus in Asia Minor. They are supposed to be descendants of Israelites who left during the wilderness years. They left Miletus for Ireland after the Persians destroyed the city in 494 BC (The Story of Celto-Saxon Israel, p 80-81).

The actual Irish legends say the Milesians were the sons of Milidh and descendants of Japeth who arrived in Ireland in 1300 BC (The History of Ireland, p 74, 106, 116). They have nothing to do with the Israelites or Miletus in Asia Minor.

After the fall of Jerusalem in 586 BC some Jews, including the prophet Jeremiah and “the king’s daughters”, who were presumably the daughters of Judah’s last king Zedekiah, fled to Egypt (Jeremiah 43:6). The Bible does not say what happened to Jeremiah and Zedekiah’s daughters, however British-Israelites claim they migrated to Ireland.

British-Israelites claim that Jeremiah was known in Ireland as Ollam Fodhla (Judah’s Sceptre and Joseph’s Birthright, p 250, Jacob’s Pillar, p 31). Ollam Fodhla was an Irish king, a descendant of Milidh who was a descendant of Japheth. He killed the previous king Ailldeargoid and reigned for 30 years (The History of Ireland, p 133). This does not sound like the prophet Jeremiah.

British-Israelites claim that Zedekiah’s daughter Tea-Tephi married the Irish king Herremon or Erimon who was a descendant of Judah’s son Zarah. Thus, the Irish kings, and later the Scottish and English kings, are supposed to be the descendants of king David (R. F. A. Glover, England, The Remnant of Judah and the Israel of Ephraim, Rivington, London, 181, p 77-90, Judah’s Sceptre and Joseph’s Birthright, p 228-229, 267-269).

However, The Annals of the Twelve Masters says that Erimon was the son of Milidh and Scota, the daughter of Pharaoh. Tea was the daughter of Lughaidh, son of Ith. Tea married Erimon in Spain before the Milesian invaded Ireland (The Annals of the Twelve Masters, M3500.1, M3502.2)

British-Israelites have butchered the Irish legends. Tea was the daughter of Lughaidh, son of Ith, not Zedekiah, son of Josiah. Her mother-in-law was the daughter of an Egyptian Pharaoh. Tea married Erimon in Spain, not Ireland and he was a descendant of Magog, son of Japheth, not Judah’s son Zarah. This is supposed to have taken place around 1300 BC, not after the fall of Jerusalem in 586 BC.

Jeremiah is also supposed to have taken the stone, which Jacob used as a pillow at Bethel when he had a vision of a ladder coming down from Heaven (Genesis 28:10-17), with him to Ireland.

Many British-Israelites believe that Jacob took the stone down to Egypt. The Israelites took it with them during the Exodus and it was used to crown the kings in Jerusalem. When Nebuchadnezzar conquered Jerusalem, Jeremiah took it to Egypt and then to Tara in Ireland. None of this is in the Bible.

In Ireland Jacob’s stone was known as Lia Fail and it was used to crown Irish kings. In 500 the Lia Fail was taken to Scotland where it was called the Stone of Scone or Stone of Destiny or Coronation Stone. Scottish kings were crowned on it until 1296 when Edward I took it to Westminster Abbey where English monarchs were crowned on it. (Jacobs Pillar)

An obvious problem with this theory is that the Lia Fail and the Stone of Destiny are two different stones. The Lia Fail was not taken to Scotland. It is still at Tara in Ireland (Nick Aitchison, Scotland’s Stone of Destiny, Tempus, Gloucestershire, 2003, p 18).

Moreover, the earliest surviving accounts of the stone’s origin do not say that the Scots were Israelites or that the Stone was Jacob’s pillow. In 1301 Baldred Bisset wrote in Processes that Scota was the daughter of an Egyptian Pharaoh who travelled with her fleet and the “royal seat”, which was presumably the Stone, to Ireland and then to Scotland. (Scotland’s Stone of Destiny, p 20)

Around 1370-1380 John of Fordo wrote in the Chronicle of the Scottish People that Gaytheos, son of a Greek king, travelled to Egypt where he married Scota, Pharaoh’s daughter. Gaythelos refused to pursue the Israelites during the Exodus so he and other Greeks and Egyptians were expelled from Egypt. Gaythelos went to Spain where he died, but his sons travelled to Ireland. Their descendants migrated to Scotland (Scotland’s Stone of Destiny, p 28-29).

John Fordun recorded two versions about the origin of the Stone. One said that it was made in Spain. The other said Gaythelos took it with him from Egypt ( Scotland’s Stone of Destiny, p 22).

La Piere d’Escoe, written after 1307, says that at Moses’ instigation Gaidelon and Scota , Pharaoh’s daughter, brought the Stone when they left Egypt and went to Scotland (Scotland’s Stone of Destiny, p 24-25).

In 1296 Edward I defeated the Scots and took the Stone to Westminster Abbey. Around 1327 William Rishinger in Chronica et Annles was the first to claim that the Stone was Jacob’s Pillow (Scotland’s Stone of Destiny, p 123). Rishinger was English, not Scottish, so it appears that the idea the Stone was Jacob’s Pillow was invented by the English to undermine the Scottish version.

Geologists have concluded that the Stone is a Lower Old Red Sandstone from the Scone area. It does not come from the Middle East (Scotland’s Stone of Destiny, p 48-49

Raymond Capt says that in the Declaration of Arboath or Scottish Declaration of Independence, which was addressed to Pope John XXII in 1320, the Scots “claim descent from the Israelites in Egypt.” (E. Raymond Capt, Scottish Declaration of Independence, Hoffman, Muskogee, 1996, p 44)

In fact, it says the Scots came from Greater Scythia, migrated to Spain and arrived in Scotland “twelve hundred years after the people of Israel crossed the Red Sea.” (Scottish Declaration of Independence, p 41) It does not say the Scots were Israelites, only that they arrived in Scotland 1200 years after the Exodus, that is, around 250 BC.

British-Israelites can present no reliable historical evidence to support their theory. There are no ancient English, Scottish or Irish writers who believed they were the descendants of the lost tribes. They have made up groundless claims ad hijacked and misrepresented myths to support their claims.

If western Europeans are not the lost tribes, there is still the question of what happened to the ten northern tribes of Israel.

First, we need to understand that Judah and Israel were not necessarily “two separate and distinct nations” (The Story of Celto-Saxon Israel, p 44) as British-Israelites maintain.

During the reign of King Asa of Judah (912-871 BC) “great numbers” of pious Israelites from Ephraim, Manasseh and Simeon defected from Israel to Judah (2 Chronicles 15:9).

In 722 BC the Assyrians captured Samaria and the last deportation of the northern tribes took place, however during the reign of King Josiah of Judah (649-609 BC), there was still a “remnant of Israel” (2 Chronicles 34:9), who were present for the Passover. They were presumably refuges from Israel who had escaped to Judah. Archaeological evidence shows that towards the end of the 8th century BC, the city of Jerusalem expanded. This is presumably because refugees from Israel had resettled in Jerusalem (Hershel Shanks, Jerusalem An Archaeological Biography, Random House, New York, 1995, p 79-81). Both the Old Testament and the archaeological evidence suggest that not all the northern tribes were deported by the Assyrians. Some were assimilated into the southern kingdom of Judah.

It also appears that some members of the northern tribes of Israel returned with the Babylonian exiles to Jerusalem. Ezra records a letter of the Persian king Artaxerxes saying, “I decree that any of the people of Israel or their priests or Levites in my kingdom who freely offers to go to Jerusalem may go with you.” (Ezra 7:13)

1 Chronicles says that after the Exile, “some of the people of Judah, Benjamin, Ephraim and Manasseh lived in Jerusalem.” (1 Chronicles 9:3)

In Ezra and Nehemiah those, who returned to Israel, are repeatedly referred to as Israel.

In the New Testament Anna of the tribe of Asher was in the Temple in Jerusalem when the baby Jesus was presented (Luke 2:36-38).

Clearly, not all the northern tribes returned. 2 Kings says, “Israel was exiled from their own land to Assyria until this day” (2 Kings 17:23). 1 and 2 Kings were written after 561 BC when Jehoiachin was released from prison (2 Kings 25:27), so it appears the Israelites were still in the former Assyrian territory then.

1 Chronicles says that the Assyrians deported “the Reubenites, the Gadites and the hall-tribe of Manasseh, and brought them to Halh, Habor, Hara, and the river Gozan, to this day.” (1 Chronicles 5:26)

1 and 2 Chronicles were written around 400 BC at the earliest, so the Israelites must have still been where they had been deported as late as 400 BC. This contradicts the British-Israel claims that the Israelites had already left and were now called the Scythians.

Around 90-100 AD Josephus wrote that the northern tribes were still in the same area beyond the Euphrates;

“But then the entire body of the people of Israel remained in that country, wherefore there are but two tribes in Asia and Europe subject to the Romans, while the ten tribes are beyond the Euphrates til now. And are an immense multitude, and not to be estimated by numbers.” (Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews,11:5:2)

This would presumably place the Israelites in Mesopotamia at the same time the Romans were fighting the Germanic tribes in Europe. Again, the historical evidence suggests they were two different groups of people.

Josephus also wrote that there were large numbers of Jews “beyond the Euphrates” (Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, 15:2:2, The Jewish War, 0:2, 6:6:2). He presumably did not mean there were both Jews and Israelites living separately beyond the Euphrates, rather the descendants of the northern nation of Israel had come to also refer to themselves as Jews.

This is evident at Pentecost when “devout Jews from every nation under heaven” were visiting Jerusalem (Act 2:5). This included “Parthians, Medes, Elamites and residents of Mesopotamia, Judea and Cappadocia, Pontus and Asia, Phrygia and Pamphylia, Egypt and the parts of Libya belonging to Cyrene, and visitors from Rome, both Jews and proselytes, Cretans and Arabs.” (Acts 2:9-11)

Peter referred to these pilgrims as both “men of Judah” (Acts 2:14) and “Israelites” (Acts 2:22,29).

In his defence speech before Agrippa Paul said, “And now I stand here on trial on account of my hope in the promise made by God to our ancestors, a promise that our twelve tribes hope to attain, as they earnestly worship day and night.” (Acts 26:6-7)

It does not sound like Paul believes ten of the twelve tribes are lost. They are united and still worshipping God. They are not barbarian tribes outside the Roman Empire.

Likewise, James addressed his epistle “To the twelve tribes in the Diaspora” (James 1:1) who meet in synagogue (James 2:2). The Diaspora refers to the dispersion of the Jews in the ancient world. James is apparently saying the Diaspora includes all twelve tribes who are now designated as Jews.

It looks like the Jews and Christians of the first century AD did not think the ten tribes of Israel were “lost”. They were now also called Jews, identifying with the kingdom of Judah.

In a 2003 article “Israelites in Exile” In Biblical Archaeological Review, K Lawson Younger cites examples of Assyrian clay tablets where the fathers had Israelite names but their sons had Assyrian names. This suggests that many Israelites were gradually assimilated and lost their Israelite identity (K. Lawson Younger, “Israelites in Exile”, Biblical Archaeological Review, November/December 2003, p 66).

There could be people in the Middle East today who are the descendants of the northern tribes of Israel, but they have idea, much in the same that other nations in the Old Testament, such as the Edomites and Moabites, lost their national identity, but it is still possible they have descendants in the Middle East today.

Reblogged this on James' Ramblings.

Can I ask about some british isreal claims?